Fans Create Awesome Season 2 for Berserk 1997 Anime

“Berserk” has had quite a tumultuous journey when it comes to its anime adaptations. It all started back in 1997 with a series that introduced us to the intense world […]

“Berserk” has had quite a tumultuous journey when it comes to its anime adaptations. It all started back in 1997 with a series that introduced us to the intense world […]

Viewers were introduced to Shin and his brave attempts to change the game for the first time in the first episode of The New Gate. After escaping the dangerous game […]

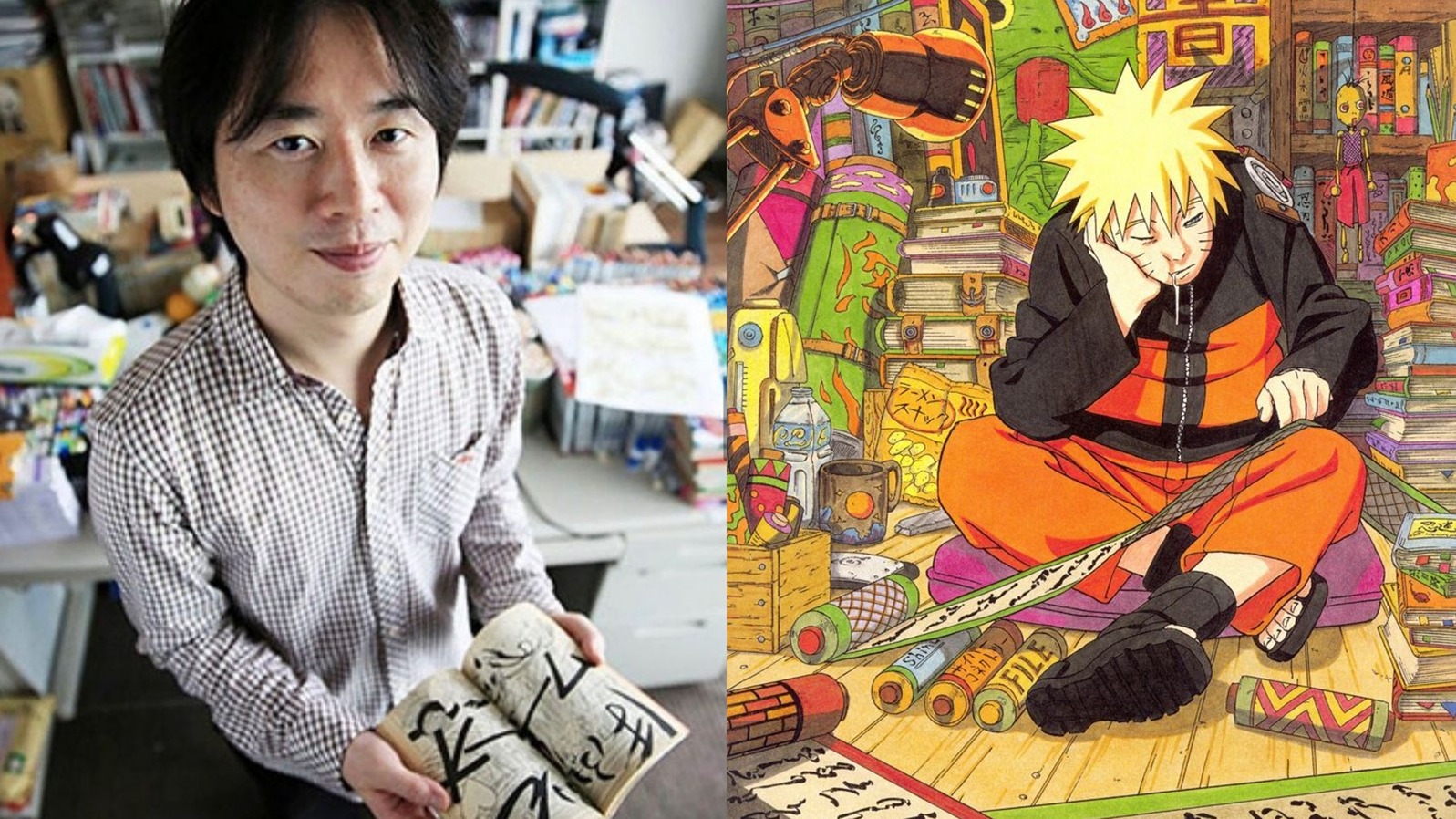

Masashi Kishimoto, the renowned creator of Naruto, will step into the spotlight with a rare appearance at a convention in France. Fans around the world are eagerly awaiting the chance […]

Hold on tight as My Deer Friend Nokotan introduces another quirky addition to its cast: Meme Bashame, voiced by Fuka Izumi (known as Rin Rindo in HIGHSPEED Étoile). Let’s take […]

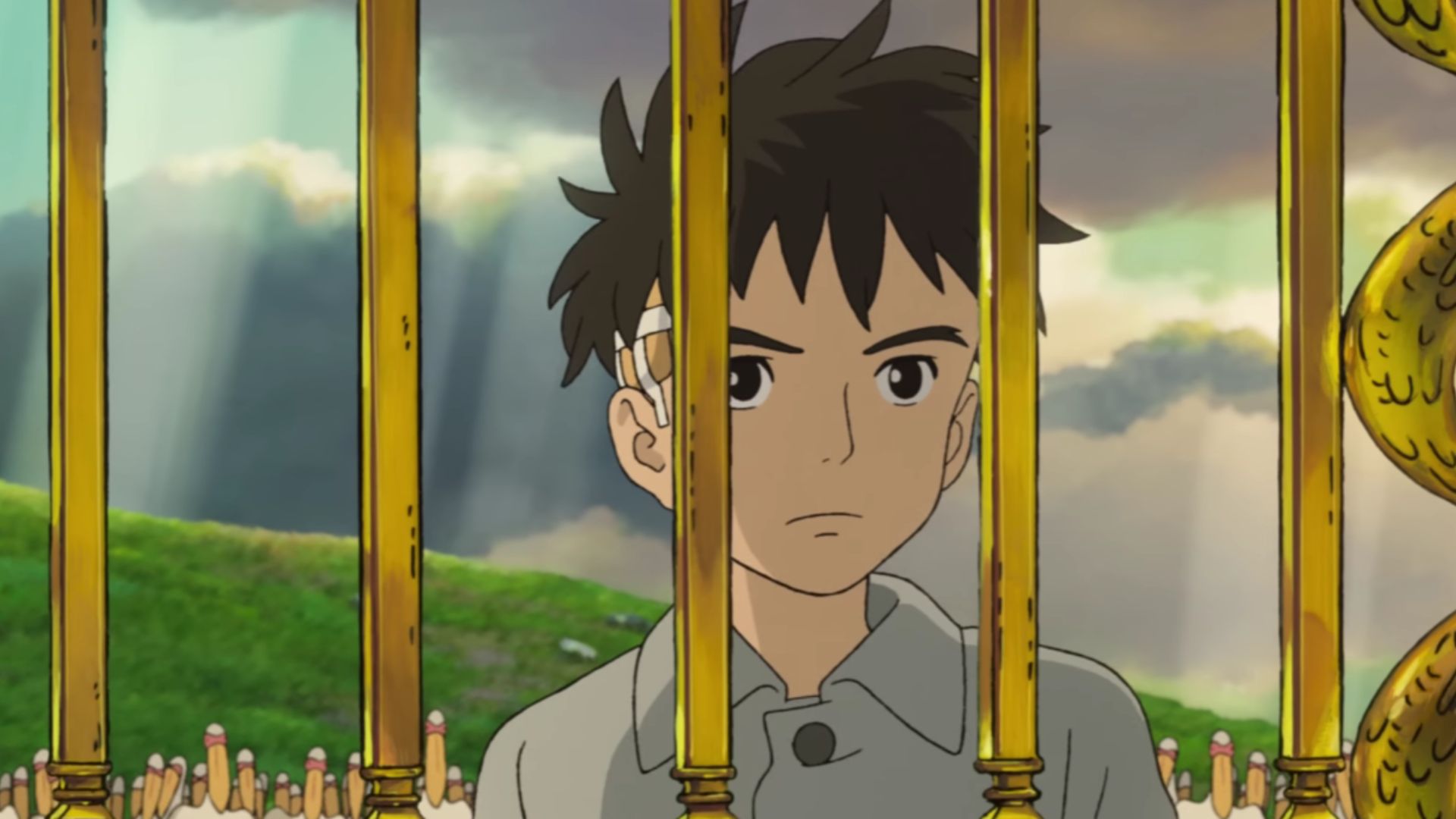

Warner Bros. India took to Twitter on Monday to announce the upcoming release of Hayao Miyazaki’s latest feature film, The Boy and the Heron, in Indian cinemas. The film will […]

Naruto Shippuden Hindi Dubbed Download Sony Yay is an anime series that follows Naruto in his next journey.(Naruto Shippuden Hindi Dubbed Sony Yay Release Date) | Naruto Shippuden Hindi Dubbed […]

Mikakunin de Shinkoukei Chapter 186 Explained: The Chapter 186 opens with Kobeni and Hakuya sitting outside at night gazing upon the stars together, admiring how lovely Kobeni finds it to […]

My Wife Is From a Thousand Years Ago Chapter 264: In the latest chapter of the manga “My Wife is from a Thousand Years Ago”, the story continues to follow […]

A new anime called Astro Note will hit the screens soon. Created by Telecom Animation Film and Shochiku. This original series follows the journey of Miyasaki Takumi as he takes […]

Takako Shimura took to Twitter on March 21 to announce that Hitorigurashi’s previously published Futari (Living Alone Together) one-shot manga will receive regular serialization. The series will debut in the […]