The New Gate Episode 2: Release Date, Recap & Spoilers

Viewers were introduced to Shin and his brave attempts to change the game for the first time in the first episode of The New Gate. After escaping the dangerous game […]

Viewers were introduced to Shin and his brave attempts to change the game for the first time in the first episode of The New Gate. After escaping the dangerous game […]

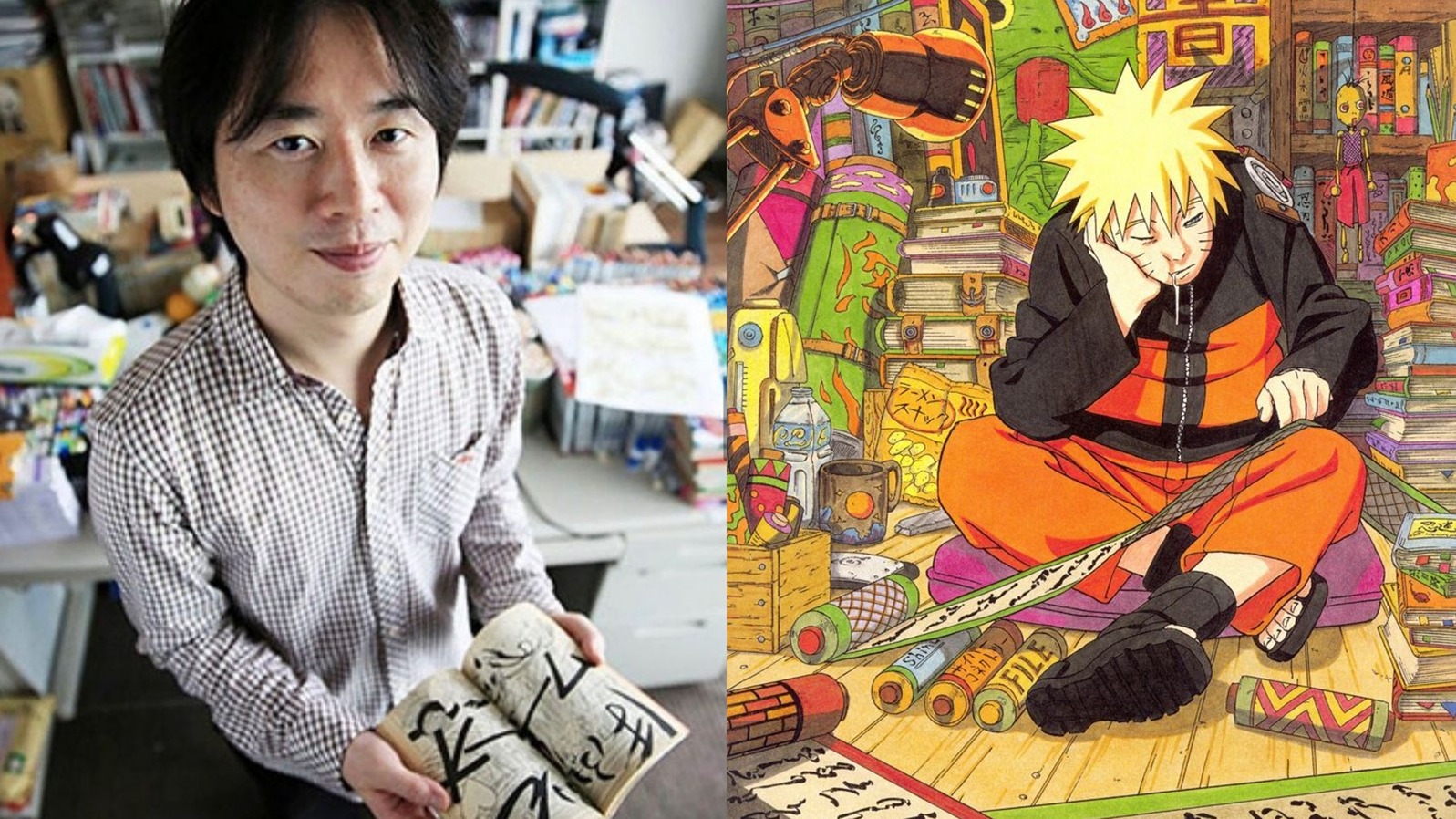

Masashi Kishimoto, the renowned creator of Naruto, will step into the spotlight with a rare appearance at a convention in France. Fans around the world are eagerly awaiting the chance […]

Hold on tight as My Deer Friend Nokotan introduces another quirky addition to its cast: Meme Bashame, voiced by Fuka Izumi (known as Rin Rindo in HIGHSPEED Étoile). Let’s take […]

Warner Bros. India took to Twitter on Monday to announce the upcoming release of Hayao Miyazaki’s latest feature film, The Boy and the Heron, in Indian cinemas. The film will […]

Naruto Shippuden Hindi Dubbed Download Sony Yay is an anime series that follows Naruto in his next journey.(Naruto Shippuden Hindi Dubbed Sony Yay Release Date) | Naruto Shippuden Hindi Dubbed […]

Mikakunin de Shinkoukei Chapter 186 Explained: The Chapter 186 opens with Kobeni and Hakuya sitting outside at night gazing upon the stars together, admiring how lovely Kobeni finds it to […]

My Wife Is From a Thousand Years Ago Chapter 264: In the latest chapter of the manga “My Wife is from a Thousand Years Ago”, the story continues to follow […]

A new anime called Astro Note will hit the screens soon. Created by Telecom Animation Film and Shochiku. This original series follows the journey of Miyasaki Takumi as he takes […]

Takako Shimura took to Twitter on March 21 to announce that Hitorigurashi’s previously published Futari (Living Alone Together) one-shot manga will receive regular serialization. The series will debut in the […]

Jujutsu Kaisen stands out as one of the most beloved shonen series of our time, celebrated for its gripping action, intricate power system, and diverse, memorable characters. Centered around Yuji […]